It's time to shine a light on Golden Triangle rail.

Half of the population of Aotearoa lives north of Taupō and the four Upper North Island regions are projected to have two-thirds of Aotearoa’s population growth in the coming decades. It's an obvious area for rail investment.

REGIONAL RAILCONNECTIONWAIKATO

Darren Davis & Malcolm McCraken

5/1/20237 min read

This weekend saw some great news with the announcement of central government funding to support the purchase of new fleet of 18 hybrid trains to replace the ageing and life-expired lower North Island rolling stock. This will enable, for the first time in many decades, better connectivity by public transport between the Manawatū, Horowhenua, northern Kāpiti, the Wairarapa and Wellington. This includes service outside of traditional commuter peaks and will add new weekend service to Palmerston North and improve weekend service on the Wairarapa Line.

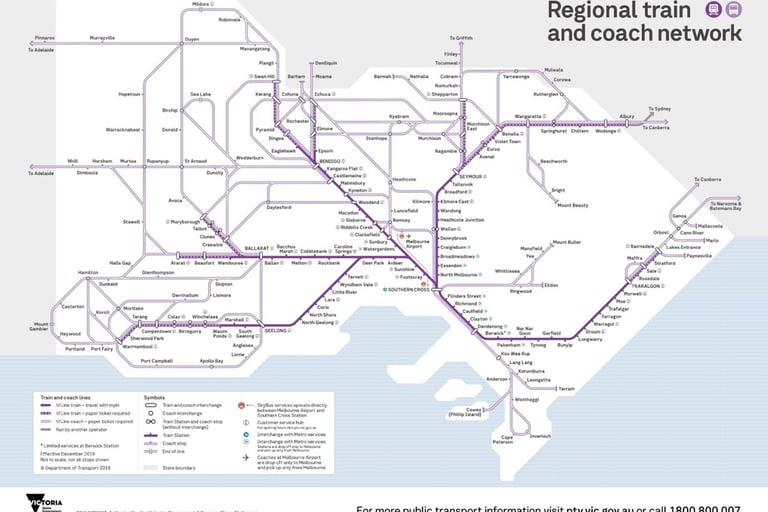

This will deliver the first tender shoots of what regional rail could provide in terms of low-carbon, inclusive access for the lower North Island and in fact for all of Aotearoa. In Australia, the state of Victoria has demonstrated this through sustained and ongoing investment in regional rail from the turn of this century. Just prior to the pandemic, regional trains (and connecting coaches) carried 22.4 million passengers a year through a connective state-wide network of trains and coaches.

It has to be acknowledged that this achievement didn’t come cheap to Victoria because they too had to invest heavily to recover from decades of under-investment and neglect in their rail network. But with a two-decade head start on Aotearoa, they have built, and continuously improve, a regional rail and public transport network that strongly supports Melbourne as the state capital and strong regional cities that are well connected to Melbourne.

For Aotearoa to embark on the next stage of a rail revival journey requires building on the great initial step of investing in new regional rail rolling stock for the Lower North Island. To support the investment in rolling stock, we need to see how KiwiRail, the government and regional authorities plan to deliver on the Wellington Rail Programme Business Case, which provides a rail development pathway for the Hutt Valley and Kāpiti lines that supports urban, regional, long-distance and freight rail development in the Lower North Island.

Following the Lower North Island, the obvious next place to look is the Upper North Island. Half of the population of Aotearoa lives north of Taupō and the four Upper North Island regions are projected to have two-thirds of Aotearoa’s population growth in the coming decades. The vast majority of that population and growth is in the so-called ‘Golden Triangle’ of Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga.

Opportunities have already been missed to provide fast-growing communities in the North Waikato with access to existing and future rail services. For example in 2005, Pōkeno had a population of just 500. By 2021, that number had increased by 341% to 5,545 with growth continuing unabated. According to 2018 Census data, 666 Pōkeno residents commuted to work in Auckland, a number that has likely significantly increased since then. At present, the first bus from Pōkeno at 6:10am would get you to Britomart Station in Downtown Auckland at 8:46am by connecting to another bus at Pukekohe which connects to the train at Papakura, while Google Maps estimates a car travel time of up to 2 hours and 10 minutes, which is not much better. The Te Huia Hamilton to Auckland train passes through but does not stop in Pōkeno. But if it did, it would take well over an hour off the current public transport travel time.

Similarly, Te Kauwhata’s current population of 2,760 is projected to triple over the next eight years with 1,600 new homes being developed by Winton and Kāinga Ora . This significant residential population increase is not accompanied by a commensurate increase in nearby employment meaning that most residents are required to commute to areas with substantial employment, such as South Auckland and Hamilton. Currently, Te Kauwhata has just two weekday bus services to Hamilton, taking just under an hour and a half and a single weekday bus service to Pukekohe, taking an hour. Te Huia, if it stopped, would take around an hour and a quarter to Puhinui and 40 minutes to Rotokauri Station in Te Rapa, Hamilton.

While growth is more muted in Tūākau, there is strong support there for the town to be once again served by rail. Tūākau has a population of 5,890 with a higher-than-average growth rate which could see the population almost double by 2031. At the 2018 Census, 1,113 people left Tūākau for work with the vast majority going to Auckland.

Ngāruawāhia also presents a good opportunity for a revived station location as one platform still exists at the former station site. The town is the kick-off point for the Te Awa cycleway to Hamilton, Cambridge and beyond and is a key site for Waikato Tainui with the Turangawaewae Marae, Kingitanga Reserve, Turangawaewae House and the Puke-i-aahua Pā site.

As is typical in Aotearoa, these towns have been developed with the usual car-based infrastructure in place as a matter of course but with lagging and very limited public transport provision. But all were railway towns back in the day and in their heyday, there were over 36,000 rail trips a year from Tūākau, 16,000 rail trips a year from Te Kauwhata and 19,000 rail trips a year from Pōkeno.

While there is no trace of the former Pōkeno Railway Station, concept work has been carried out by Waikato District Council about a potential station site and in Te Kauwhata, the station platform and pedestrian access still exists, albeit in a rather rundown state; the Tūākau Station island platform still exists as does one platform at Ngāruawāhia Station.

While the Te Huia Hamilton to Auckland train had its second-best month ever in March 2023, carrying 7,120 passengers, the fact that its last boarding stop is in Huntly, ninety-three kilometres from Auckland and that it does not pick up passengers anywhere in the Auckland commuter belt, means that it is not achieving its full potential. There is clearly a substantial existing and potential market of residents for this service in each of these communities which are a long way from employment. Serving them would make best use of the committed investment in Te Huia as well as providing sustainable transport choice to fast-growing communities in the North Waikato. We understand there is initial work underway investigating the potential for stations in all three towns.

In all of this, it has to be remembered that the only way for Te Huia to recover its sunk cost in infrastructure is to make use of it to carry people. Having additional station stops on the route where there is considerable population growth would be a good start. Similarly to the existing rolling stock in the Lower North Island, Te Huia makes use of recycled 1970s Mark II carriages from the United Kingdom, previously recycled by Auckland as interim rolling stock until Auckland electrified its rail network in 2014-2015. As such, the current rolling stock is both close to the end of its latest and final life extension and, like the now resolved situation with the Lower North Island rolling stock, needs a sustainable long-term solution that is fit for purpose for a 21st century regional rail operation.

The Lower North Island rolling stock solution provides a template that could be expanded to provide a sustainable long-term solution for securing the long-term future for Te Huia. The extent of electrification in both Auckland and Wellington ends of the North Island Main Trunk Line is nearly identical at 56 kilometres (once Papakura to Pukekohe electrification is completed) and the extent of running on battery power is around 80 kilometres in both cases. And of course, if the electrification gap between Pukekohe and Te Rapa, in north Hamilton, were plugged, then the battery or diesel functionality would support extending the service to Tauranga or elsewhere.

An obvious consideration are the different forms of electrification between the legacy Wellington DC powered suburban network, largely developed from 1938 to 1955 and extended since in stages from Paekākāriki to Waikanae, and the more modern AC electrification of the Hamilton to Palmerston North section of the North Island Main Trunk Line and Auckland metro network. While this is a consideration, there are technologies that enable running on both AC & DC power. An example of this are the French regional trains that run from Marseille along the Côte d'Azur towards Monaco and Italy which run on DC power in Marseille and AC power elsewhere.

So, while it is great to finally see an enduring and sustainable rolling stock solution for the Lower North Island, there are real potential synergies here with creating a regional rail template that can be applied to connecting the Golden Triangle of the Upper North Island. And while this longer-term solution is being sought, there are real opportunities to make best use of the existing investment in Te Huia but adding station stops in fast growing communities in the North Waikato.

This would be a first step in building on the committed investment in Lower North Island rolling stock to start moving Aotearoa towards the sort of connective rail network, supported by feeder bus services, in the state of Victoria that carry over twenty million trips a year.

So what we are calling for is:

Urgent work on providing station stops for Te Huia to rail-served towns on its route in the North Waikato.

Leveraging the opportunity presented by the commitment for new Lower North Island rolling stock solution to provide an enduring long-term solution for the Upper North Island, including enabling service expansion to Tauranga. This could simply be an add-on option to the contract which could allow for similar rolling stock, suited to the Upper North Island network, to be purchased.

Double tracking the 15-kilometre single-track section through the Whangamarino Swamp and across the single-track Ngāruawāhia Bridge to enable more freight, long-distance and regional train service to operate at higher speeds. The Rail Network Investment Plan has a business case for work on this set down for the 2023-2024 financial year.

Figure 4: Te Kauwhata Railway Station. Credit: Darren Davis

Figure 3: Tūākau Rail Support Billboard. Credit: Darren Davis

Figure 1: Victorian Train Network Map. Credit: Public Transport Victoria

Figure 2: Pōkeno continues to grow. Credit: Darren Davis