Mind the gap

Every transport-related conversation should start with the question, ‘how will this give us hope to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming?’

CLIMATE CHANGE

Paul Callister and Robert McLachlan

3 min read

Every transport-related conversation should start with the question, ‘how will this give us hope to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming?’. But there remains a big gap in thinking. Motorway and airport expansions are still being promoted despite the clear evidence that they will increase emissions.

The need for rapid and substantial emission reductions was in the background in many of the presentations given at the Future of Rail conference. But it was only Roman Shmakov, representing Generation Zero, who specially asked why long distance and regional passenger rail is absent from the Government’s transport policy documents. These come primarily from the work of the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of the Environment, and the Climate Change Commission. They include the 2021 Rail Plan, the Emission Reduction Plan and advice to government on how best to reduce emissions.

This is despite the overwhelming evidence that trains are substantially lower emissions than planes. In addition, trains’ energy use is substantially lower, an advantage that will continue even if passenger electric planes shift from prototypes to actually flying commercially. Power to fuel as an alternative to fossil fuels would also require huge amounts of renewable electricity, as would the direct use of hydrogen.

Now the Inquiry into the Future of Inter-regional Passenger Rail in New Zealand has released its report. Clearly many submitters saw trains as a key means for reducing emissions and the report acknowledges this.

But the gains will only come about if:

We quickly rebuild our passenger rail network.

We have a substantial modeshift from cars and planes to trains.

We can rebuild the network. But will people use the trains?

The presentations at the conference presented a wide range of potential train revivals, from linking up the golden triangle of Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga, relinking South Island towns and cities along existing rail tracks, through to more aspirational ideas such as a train/ferry link to Queenstown. There was also recognition of the first/last mile problem to make trains easier to access. Housing intensification around rail hubs was also touched upon creating a potential market to draw upon.

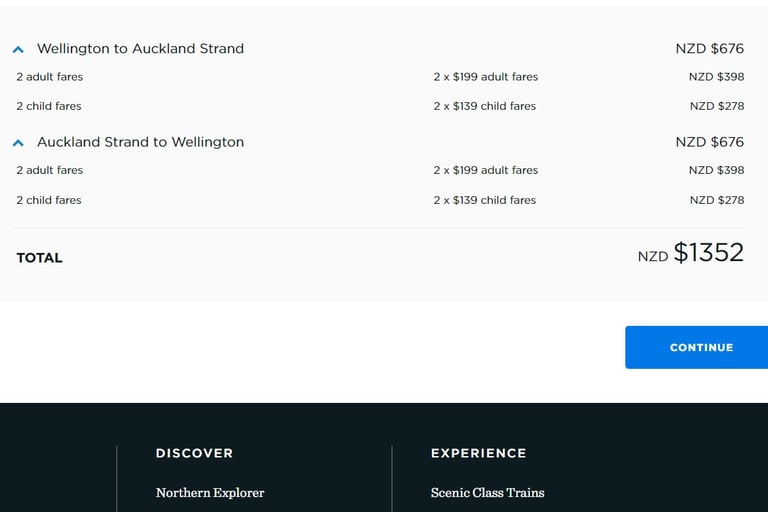

Pre-conference blogs highlighted the untapped markets for train travel, such as the transport-disadvantaged with limited regional travel options and teenagers. The high cost of the current tourist trains, along with their infrequent schedules, makes them impossible for most families.

Source: Great Journeys of New Zealand website.

But missing from the conference day were many other aspects of the sweeping, systemic changes that the IPCC repeatedly finds are necessary for a safe future.

Models of Growth

There is an emerging debate between traditional economic growth, green growth and degrowth. In the decarbonisation model of Avoid/Shift/Improve, traditional growth relies almost entirely on ‘improve’. It may pay lip service to planetary boundaries but assumes that innovation and productivity will solve the problems. Road building and expansion of airports will stimulate the economy and lift standards of living. Trading schemes, such as the ETS, will solve emission challenges. If there is an impending shortage of particular minerals to support this growth, pricing and science will ensure that we swap to new alternatives. Unfortunately, these views, unsupported by science, are behind the view that in Aotearoa New Zealand long-distance trains are as part of the past, not the future. This was the view of Treasury as it drove restructuring of the economy after 1984. Treasury was not present at the conference.

Green growthers also rely heavily on technological innovation, but focus on both ‘Shift’ and ‘Improve’. For them, new types of trains, planes, and fuels lead the way for long distance mobility. Degrowthers focus primarily on ‘Avoid’ and ‘Shift’, placing a much higher weight on the efficiency of resource and energy use and the social purpose of travel. Trains are a key part of future mobility.

These discussions were not a key part of the conference. Yet if the conventional economic model is doomed to failure, we need to explore the alternatives.

Urban design, roads, and sprawl

Many of the talks at the conference provided a vision of how we can grow our population and housing stock along rail corridors. In fact, the word ‘growth’ – economic and population growth – was heard repeatedly as part of arguments for investment in passenger rail. It was cited as a key reason for getting the improved services in the lower North Island over the line. But growth is a double-edged sword. Taking the Capital Connection as an example, do we really want 150 km of sprawl and strip development from Wellington to Manawatū, even if the old town centres are linked by improved passenger rail? This becomes even more problematic when combined with the present push for continued expansion of the road and motorway network, further encouraging long-distance commuting and sprawl.

These are essential issues, even if they are too much for the humble train to tackle all by itself. There was mention at the conference of the overall car bias of the transport system. But the underlying question – can we achieve a high-quality passenger rail network without addressing car bias – remained unanswered.