Solving our regional mobility crisis

More flights and better roads do little to solve the regional mobility crisis. Passenger trains, coupled with an improved long-distance bus network, restore mobility for New Zealanders throughout the country. Climate change and economics are further reasons for investing in the public transport networks, rather than in aviation and roads.

POLICYRESILIENCECLIMATE CHANGEPUBLIC TRANSPORTREGIONAL RAILNIGHT TRAINSINFRASTRUCTURETHE FUTUREINVESTMENT

Paul Callister & Heidi O'Callahan

9/26/20257 min read

Source: Peter Paul Rubens / Jacob Peter Gowy - Wikipedia

Flying was fantasy, once. For fools with faith in feathers.

After its mysteries were puzzled out, and technological development led to commercial aviation, the status of flying shifted from “foolish” to “fancy”, to “essential” for the wealthy. It remains, globally, a minority activity; but one of the most carbon-intensive.

Do New Zealanders now consider flying a “right”? Media articles would suggest complaints have replaced awe and gratitude; passengers whinge about fares, airlines claim regulatory costs are too high, and regional airports now seek subsidies from local ratepayers. Aviation, it seems, is not proving economically viable for some smaller cities and towns.

These media articles do, at least, acknowledge a current regional mobility crisis. Options for getting around are limited. Outside the main urban centres, the transport services and infrastructure needed for basic errands, education, healthcare, social interaction and recreation, are often missing. This applies to both basic trips within the local region, and to longer inter-regional trips.

Aviation is not a good solution for the shorter trips. For many longer trips, the innumerable pairs of origin and destination towns (most of which have never had a commercial airport and never will) also render it impractical. On top of this, aviation is inequitable. It imposes social costs, like climate damage and noise, that are in no way mitigated by any duties included in the fares.

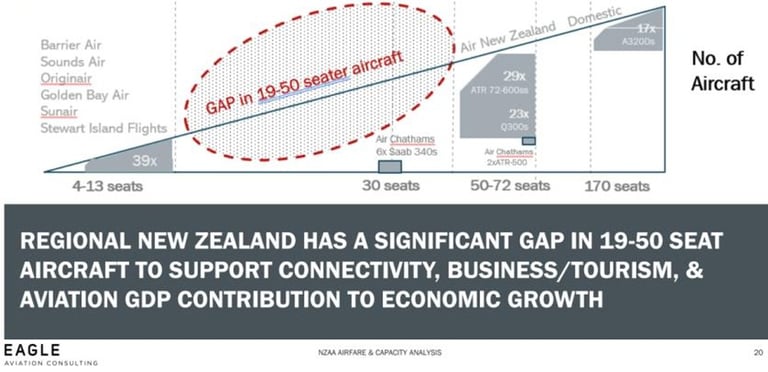

A 2025 WSP report prepared on behalf of the Airports Association identifies many challenges facing regional aviation. One is a looming gap in the availability of new planes carrying 19 to 50 passengers (pg 19).

Our regional mobility crisis is peculiar. Unlike most other developed countries, New Zealand has come to rely almost solely on flying and driving for regional mobility. Even in places like the United States and Australia, where cars and planes are also king, core coach and train networks have not only been retained but are being improved.

In the decades prior to Covid, New Zealand saw a remarkable growth in domestic and international aviation, and in driving. As domestic aviation and driving were increasing, alternative forms of longer distance travel were collapsing.

Often, the availability of cars and commercial flights has been cited as the reason for the demise of public transport, to the exclusion of all others.

Yet in other countries, those factors did not result in such a dramatic decline in rail and coach services. Rather, it was a lack of consistent planning and basic investment that led to the collapse of New Zealand’s regional public transport. One author who has detailed the process is André Brett, in his book, “Can’t Get There from Here.”

Now aviation is collapsing in some regions, but the sector retains ambitions for growth. Taupo airport, for example, has seen taxpayer and ratepayer-funded upgrades but there is insufficient demand to support flights to Wellington. The WSP report prepared on behalf of the Airports Association describes Taupo as “vulnerable to service reductions”, yet also reports the airport is wanting further upgrades, to cater for private jets. In the centre of town at the busy InterCity bus interchange, meanwhile, passengers wait with their luggage in the open air for their bus.

Taupo long distance bus stop

Restoring a functioning national public transport network should not be political. Unfortunately, transport investment is being decided politically rather than for reasons of sound economics. We saw this at the Future is Rail conference in 2023. Christopher Bishop, now Transport Minister, said we do not need more regional passenger trains, as there are already “good” long-distance coaches in New Zealand.

What New Zealand has is affordable long-distance coaches. Complaints in the media about the cost of flying from Tauranga to Wellington did not mention the option of taking the daily InterCity bus, for fares starting from $40.

But price is not everything. Those who regularly travel by long-distance coaches know they are not an adequate substitute for a proper train network. Recent governments have not put forward plans to bring the long-distance coach network up to a better standard, despite the small transport investment required.

What’s needed? First, we need frequent services, with timetables designed to enable increased use. We need coaches accessible to all members of society, not just those who can climb steep steps, and to those with super bladders. We need coaches which can carry bikes. We need bus stops that can be reached on foot safely, and which shelter us adequately. Currently, a rural bus stop might simply be a spot on the shoulder of a state highway, with no sign, its location described on an InterCity webpage. We need cafes with good facilities at the break stops. Eventually, too, our coaches need to be electric.

These are moderate requests.

Fundamentally, though, coaches are only part of the solution. They are suited to shorter trips, as passengers cannot get up and move around. Trains, being much more comfortable, are suited for longer distances.

However, rail doesn’t go everywhere, and some areas have too low a population density to support it. Coaches complement trains, increasing the network’s reach.

So, Bishop hasn’t grasped the nature of the network. It is not a question of choosing between rail and coach. An efficient, affordable, joined up public transport system requires both, and his government needs to invest in them both.

The Infrastructure Commission is attempting to broaden the discussion. It has singled out Finland as a country worth comparing with New Zealand, having a population (and population density) similar to ours. The country is also not much wealthier than us. Finland does public transport well, with regular coach and train services linking towns and cities.

Unlike ours, Finland’s coaches have fast wifi, onboard toilets, and are set up to carry people with disabilities. One bus company even offers a parcel delivery service. The supporting infrastructure (like bus stops and waiting rooms) is better than New Zealand’s.

Finnish trains carry pets, bikes, wheelchairs and some services have carriages with play areas. They have cafes and onboard toilets.

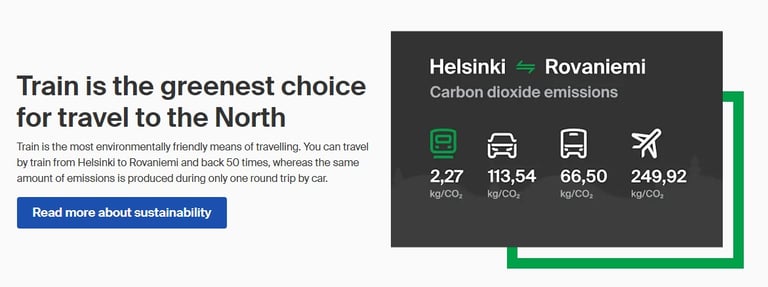

They are promoted as contributing to a reduction in transport emissions. This is made easier by much of the network being electrified.

These are real here and now reductions offered by rail. In contrast, the reductions in aviation emissions are primarily aspirational and mostly in the far distance. In a just released report on New Zealand’s aviation sector there is much talk about ‘sustainable aviation fuel’. But little in the way clear goals and plans including timelines. This report, and most other aviation documents, has its focus on ‘net zero’ out in 2050 (pg19).

“New Zealand has committed to ICAO’s global Long-Term Aspirational Goal (LTAG) of Net Zero by 2050 and the intermediary goal to reduce CO2 emissions in international aviation by 5 per cent by 2030. New Zealand is voluntarily participating in ICAO’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), a global market-based measure for reducing and offsetting carbon emissions in the international aviation sector.”

Trains are already well set up to cater for people with a range of disabilities. But the Finnish passenger train operator also notes “If you have an illness or injury and you need assistance during your journey, you may be eligible for a free assistant’s ticket.”

The example of Finland demonstrates it is possible to provide passenger rail between cities such as Auckland and Tauranga. For comparison, consider Oulu, in the north of Finland, and Tampere in the south.

Such a network is clearly within New Zealand’s reach, yet is rarely discussed by our commentators, journalists, policy makers or politicians. Perhaps this can be understood by how they travel themselves? Some may use metro trains in Auckland or Wellington. For their longer trips, though, media comments by people in these demographics typically mention frequent flying, and the Koru Club. Between smaller towns, there’s talk of driving, but never of taking an InterCity bus.

It seems that to those controlling the public discussion, public transport in the regions is invisible.

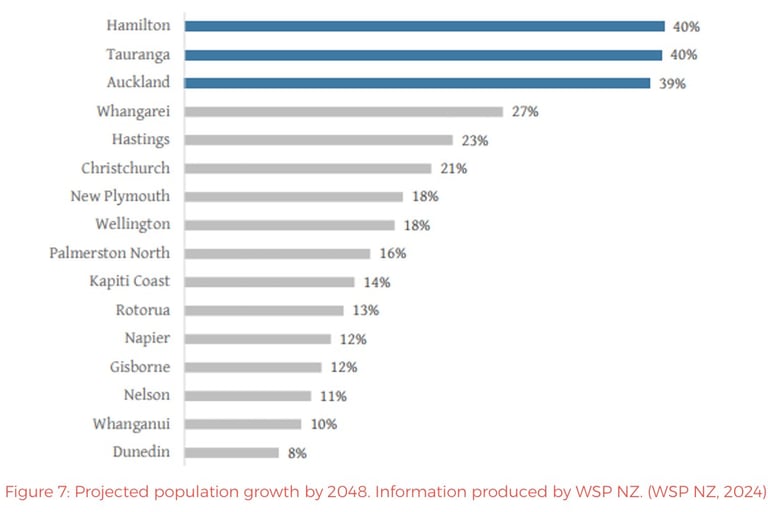

Climate change, mobility and economics are all excellent reasons for New Zealand to bring longer distance passenger trains back to many areas of New Zealand. Auckland to Tauranga. Christchurch to Dunedin. Wellington to Napier. The WSP report for the Airports Association identifies Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga in the Golden Triangle as projected to be New Zealand’s fastest growing populations. Five urban areas, all along the North Island’s Main Trunk Line, are also projected to be growth areas. Perfect for a night train.

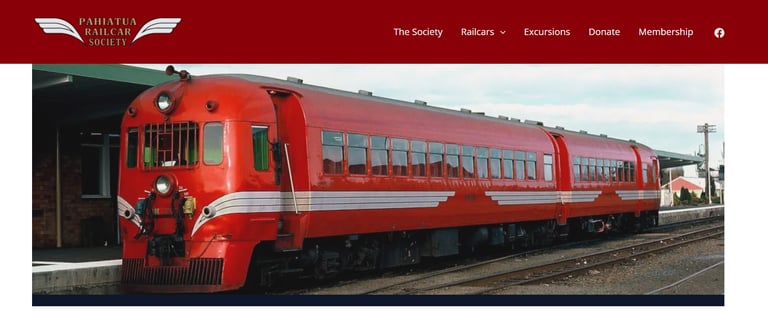

Once railcars linked many of our towns and cities. For example, twinset railcars designed by the Drewry Car Company were operating in the 1950s. The number of seats on these railcars was similar to the ‘gap’ now developing for replacement planes for regional routes.

In Finland, small railcars still operate on some routes.

In New Zealand, new trains will be arriving at the end of this decade to replace the current longer distance trains operating in the lower North Island. Versions of these newly ordered hybrid trains would be ideal for operating services in other parts of New Zealand.

These services might be a bit slower than flying, although probably not that much slower, city centre to city centre. Some people need that extra speed, but not everyone does. People can work on trains with good wifi. Trains are great for people with mobility challenges, as modern trains are designed for wheelchairs and walking frames. Easy to take a bike. Good for children and even pets.

Easier than trying to undo the damage to our climate that flying causes, and without the accompanying social subsidy.

Auckland is slightly larger than Helsinki, but Tampere and Oulu are larger than Hamilton and Tauranga. However, the combined size of the three New Zealand and Finnish cities is very similar. The distance between the Finnish cities is much greater than between the New Zealand cities.

Despite being separated by much larger distances, Finland connects all three cities with rail. If you wanted to catch a train from Tampere to Oulu during the week this September you could catch the 7.02, 8.02, 10.02, 12.02, 14.02, 15.02, 16.02, 18.02, 20.02, 23.09 or 23.59. Or you could hop on the night train coming through from Helsinki at 2.37am. If you do not catch a train, you could use a bus.